Hi, I’m James. Thanks for checking out Building Momentum: a newsletter to help startup founders and marketers accelerate SaaS growth through product marketing.

Get the next post in your inbox

Practical product marketing and GTM ideas, weekly.

I was working remotely for two weeks when we launched the new Kayako. The launch – a huge deal for the 110 employees that had been working on the new product for the last two years – happened over Google Hangouts and Slack. Everyone joined a video call, with champagne and cake ready in the offices in London and Gurgaon, India.

Everyone had a part to play – it would only happen if everyone had typed a custom command in our Slackbot to take the old marketing website down, push the new one live, and remove the restrictions, finally opening up the new product to the world.

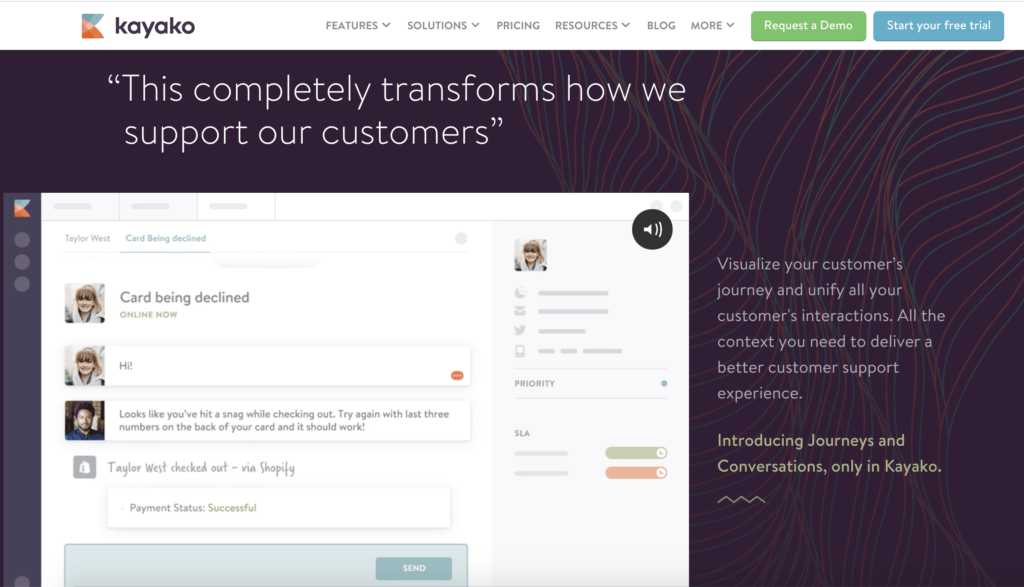

We were confident. The new Kayako was really different from anything else out there: a new customer service and live chat platform for companies that obsessed over their customer experience. It killed the concept of ‘tickets’, and instead promoted a single, effortless customer relationship across contact channels.

Our target market away from IT helpdesks and technical support teams to a new ‘customer-service-as-growth’ persona. With this, we released a new brand, pricing, and positioning. Gone was the dark blue, corporate feel that was a hangover from the 00’s; we created a brand that felt comfortable, personal, and effortless.

A few months in, that confidence had been chipped away by the reality we were facing. Low trial conversions. Product stability issues and bugs. Negative feedback. Revenue was falling. Accounts were cancelling after a few months.

We’d gone from adding thousands of dollars in new contracted monthly recurring revenue (CMRR) from the old product every month, to just hundreds.

It was bad. We got together in a war-room scenario: what was happening, and how do we fix it?

Aside from product issues, we identified areas of our go-to-market strategy that were seriously problematic. Although we had followed best practice, sought expert advice, and carried out research, we failed in three key areas: pricing, positioning, and onboarding.

In this post:

How we failed at pricing strategy, and how we fixed it

In the run-up to the launch, we had worked with a pricing consultant who’d developed best practices and frameworks from his time at Microsoft. We learnt a lot; the engagements were helpful, productive, and we felt assured and confident in the strategy.

The process involved carrying out a survey to understand the value that customers gained from our product. There was a big spreadsheet, listing each features with a dollar value against them, depending on how big of a draw it was.We drilled into competitor pricing, looking at how we compared on features and value.

In hindsight, we should have known that a pricing process developed for billion dollar corporate organizations like Microsoft could never have worked for our ~$5m ARR startup.

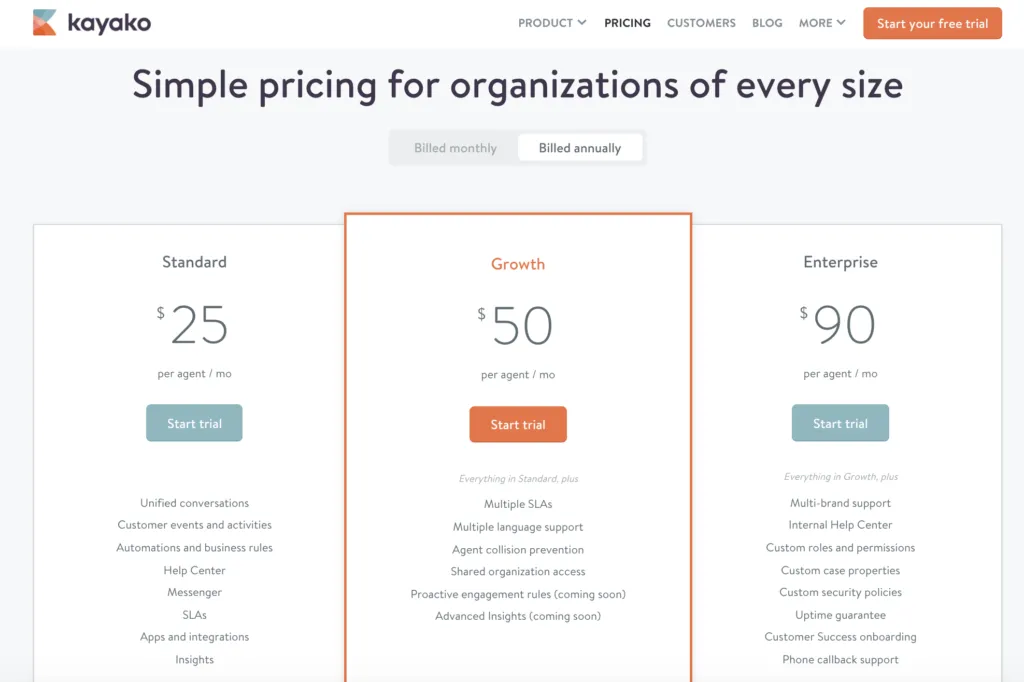

Our launch pricing strategy was simple enough. Three plans – good, better, best. Similar to our biggest competitor, although a few dollars cheaper.

We knew it was failing.

Free trial signups dropped, because they were put off by the pricing page

Conversions to paid accounts were falling, because they couldn’t experience the value they were expecting

First month cancellations were high, because customers didn’t experience the value they expected for the price they were paying

We had followed pricing best practices as instructions, not inspiration.

Immediately, we stepped up our research. We were already doing win/loss calls, which gave us a head start into the challenges we were facing. We began to call customers, prospects, and anyone that had signed up to get their feedback.

Our suspicions were correct. The pricing wasn’t working because people couldn’t see the right plan for them, at a reasonable price, that represented good value for them.

So we went back to the drawing board, starting with our target market. Who were our customers?

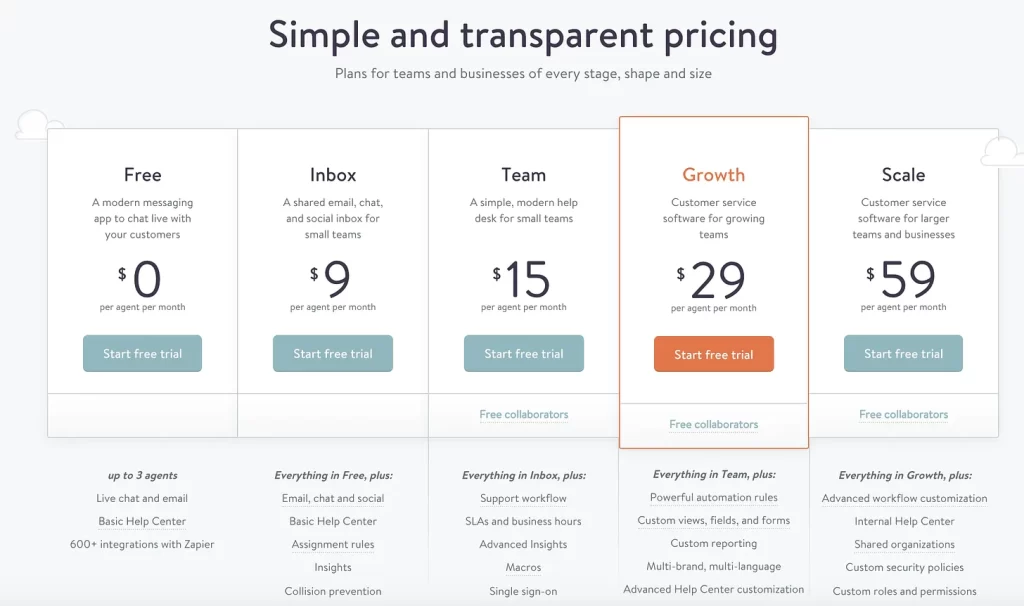

We created a spectrum of customers, from individual users that just wanted a simple live chat tool, to large teams that wanted an enterprise-level customer service platform. By mapping them out, we could see where our focus should be in the short term: building revenue from mid-sized accounts, and building volume.

We then followed a value-based pricing process from Profitwell, with three stages.

Firstly, we quantified our personas. Who were they? How profitable were they? We could do this with the data we already had.

Secondly, survey customers and people in the target market to understand the features they value the most.

Then, ask those people for four price points with a willingness-to-pay survey:

How much would be too expensive?

How much would be expensive, but not out of the question?

What price would be a bargain?

How much would be so cheap that you would question the quality?.

After analysing the results, we found that everything aligned with our customer spectrum. People who wanted a live chat tool wanted something very cheap or free. And those companies that wanted a full platform would be willing to pay significantly more.

This was a big milestone. We had turned our innate understanding of our customers into quantified, evidenced results as the basis of our strategy. We were being led by our customers.

Our original plan had been to evaluate pricing every six months. If we had waited that long, we would have been in serious trouble. After implementing the new pricing structure, we constantly gathered feedback. We analysed, cohorted, pivot-tabled the fuck out of the performance numbers to see what was going on.

Over the coming months, we adapted and tested pricing multiple times. Sometimes we offered a free plan, sometimes without. We changed the numbers, the layout of the plan, the plan names, the features included or excluded, based on what we were hearing and seeing.

We forced ourselves to iterate. And that wasn’t easy; every change took at least a day’s worth of effort from three people just to implement, let alone plan, agree, and announce.

But our ability to react quickly was the difference between success and failure.

Getting positioning wrong, and turning it around

A common best practice is to lead with aspirational, ‘world change’ messaging; and to create a category that you can own.

As part of the product launch, we wanted to set ourselves apart from competitors. We thought the most effective way to do this was by creating a narrative, using Andy Raskin’s Medium posts as a guide.

His key to creating a narrative is to define the promised land, the world that your customers can achieve when they have your product.

Naively, we used this format as instruction again, not inspiration. We tried to build a category and narrative around ‘effortless customer experience’. It was really human: no more having to repeat yourself across departments, the end of being treated like a ticket number.

When we showed this to customers and prospects, it really resonated. So we went big. The messaging united our website, collateral, and sales deck.

But after the launch, we discovered it wasn’t actually working. We found we had focused almost exclusively on this aspirational world change so much that we hadn’t covered the functional benefits that our customers expected to see (and in some cases, prioritized more).

We were alienating our customers with high-level messaging. Although we had done research and testing, we had biased ourselves towards executives and decision-makers in more mature businesses, without realising that in most cases, that wasn’t our customer.

Armed with the knowledge we had from our pricing research, we were able to pick up interviews and calls with those people that were actually interested, and were actually the correct stakeholder at different stages of the buying process.

Often, those people were at smaller companies: like co-founders that needed something they could set up easily and forget about, or an ambitious customer service professional who was looking to make big changes to the way their orgs approached customer service.

We created a single Slack channel that automatically posted every bit of good, bad, and neutral feedback we received from customers and prospects across every feedback channel. This gave us a real-time pulse check, helping us refine our mental model of who our customers were and what they cared about. We also used this to create a regular Voice of the Customer report that helped communicate this across the rest of the business.

It reduced the distance between us and our customers: a direct feed into what they cared about, and what they didn’t. We had to forget our bias, removing our impression of what we thought they wanted – and actually listened to what they were saying. We let our customers lead us.

So it was time to flex that iteration muscle again. We could test, rollout, and update new messaging really quickly. Sometimes we’d change it every day by rewriting headlines, making small tweaks, or trying something completely different.

We were lucky enough to have instant access to making website changes, along with a fantastic in-house designers and marketing developers to help. We forced ourselves to iterate and experiment – everything could be reversed if it didn’t work out, with hardly any lasting risk.

Strong relationships with our sales and success teams were crucial too, allowing us to try out new messaging, test new demo structures, and try different ways of presenting our value.

From a broken onboarding process to a smooth welcome

In the run up to launching the product, we’d researched best practices for SaaS onboarding.

The majority follow a simple rule, called time-to-value. Your product’s goal is get your customers to experience value as soon as possible, for best chance of success. It’s pretty good; it means you don’t have to focus on helping users set your product up for use, and instead you can focus on getting them to a point of satisfaction.

Our product, however, needed a lot of setup to experience value. You had to set up your support email address, connect social accounts, invite your team, set up workflows, and much more.

This was way too much to do for someone just trialling the product. But there was no substitute: you had to commit completely. But we had still followed those rules as prescribed, instead of using it as inspiration. Our first onboarding process was set up around helping users set up the account. Obviously, this was not going to be effective.

The results were disappointing. Leads were signing up for trials, looking around for a few minutes, then leaving straight away.

We couldn’t let this go on. All the work we were putting in from the marketing side to get visitors to the website… the work we had put in to iterate our messaging… the huge strides we had made with pricing… were all for nothing. We were falling down at the last hurdle.

To understand what was happening, we used Fullstory to review what users were doing in their first experience. We found that the majority of people went straight to the worst place in the product. The place where nothing looks good, where no attention was paid during development, and where things got confusing, quickly. They were going to the admin area.

We really had no idea that users would go there within the first few minutes of signing up. We had to understand why, so following this line of investigation in our calls and interviews.

We tried to find out what it was that prospects were trying to discover that they couldn’t find elsewhere. The results were interesting – users were saying they wanted to learn what features we had, and how flexible the configuration options were.

They had been interested by the website, and now we realised the first experience needed to show not just the product, but it’s potential.

So we dialled up our product education efforts. As soon as someone signed up, we showed a two minute intro video, then we hit them again with three key points to drive the message home.

We added better information in the admin menu, not just describing the technical detail, but making it clear what the potential usage of each feature could be. We carried out research to understand the most logical grouping of admin features.

We added empty stages and dummy data that demonstrated the full range of capability, without requiring any setup. Our goal was to get to a place where users could see what working in the product was like from the moment they signed up.

We didn’t get this right first time. We tried to get a balance between providing education, and getting out of the way and letting users learn and explore for themselves.

We worked with our designers and frontend developers to iterate together. As we made progress, some users weren’t happy as we tried something weird. Generally, feedback was positive. We tried to distill complexity into more simple, logical areas.

Fullstory was really useful to instantly see results, and whether users were being successful with each version we tried. When we looked at cohort data, we found a clear connection between the educational onboarding experience, and higher trial conversions.

Reacting well

It took us about six months to right these wrongs. Over that time, we had increased the new CMRR we were adding each month by other 80%. Within 18 months of launch, the new product had become a $2m ARR product, and Kayako was then acquired on the strength of it’s growth.

In each of these three examples we were able to turn around a struggling product launch, and put it back on track. Three guidelines determined our reaction.

Best practices are inspiration, not instruction

The same goes for any advice, any tips, recommendations, talks, and blog posts. There are simply too many variables, too many unknowns, and too many inherent biases at play to use a best practice or process from one situation, and expect it to perform well.

That’s not to say we can’t take inspiration from them. So long as we are applying some critical analysis to assess how we should interpret that advice.

Let your customers lead you

Doing this can feel pretty strange, however obvious. Especially if, like this product launch, you’re moving towards a new audience, a new type of customer that you don’t fully understand yet.

It’s tempting to put something out that you think will work, because you don’t know enough yet. Positioning that’s created in an internal vacuum, or pricing that’s based on your competitors.

It’s really crucial to continually build an understanding of customers all the time. Continual research over one-off projects. We have to listen, set aside our own biases, get out of our heads, and really get into theirs.

Flex your iteration muscle

I’ve called it a muscle because unless you don’t do it often, it will be hard, it will hurt, and it is going to be uncomfortable.

As marketers, I think we’re conditioned to prefer one-off, big bang launches. We do the work, launch, move onto the next thing… with plans to revisit at some point in the future.

But we’re in 2020. Nothing lasts six months anymore. Your customer’s goals, gains, pains, and jobs change much more often than we think. And so does your business strategy. What was true, and worked well yesterday, might not be true tomorrow.

We found it extremely useful to implement pulse checks: small polls, real-time feeds, and regular evaluations to keep on top of what’s happening. The goal is to test two things: if your understanding is still correct, and if your execution is still effective.

Bringing it all together

I hope this gives you a few ideas on how we approached a failing product launch, and how we turned it around by really listening to our customers, constantly iterating, and using best practices as inspiration.

Thanks for reading! Let me know what you thought: find me on Twitter and LinkedIn.

If you enjoyed this post, will you it with your network?